I. Introduction: When Data Becomes Diplomacy: In the aftermath of the Tigray war, two flagship documents from the Commission of Inquiry on the Tigray Genocide (CITG) the Productive Sector and Livelihood Assessment and the Social Sector War Damage and Loss Assessment have gained unusual authority in shaping international perceptions of the conflict. Together they claim more than 94 billion USD in total destruction, attributing the majority to the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF), the Amhara regional forces (AMF), and most prominently, the Eritrean Defense Forces (EDF).

At first glance, both reports appear technocratic and data-driven, filled with economic modeling, tables, and citations of UN methodologies. Yet beneath the surface lies a narrative that paints Eritrea as the primary foreign aggressor vindictive, destructive, and beyond reason. From an Eritrean perspective, the issue is not the reality of war’s destruction, but the political architecture of evidence: how data itself can be shaped by historical resentment, cultural bias, and geopolitical intent.

II. The Charge Sheet Against Eritrea: Across both volumes, the EDF is consistently presented as the second-largest and, in some sectors, the leading perpetrator of damage. The Social Sector Executive Summary states for example:

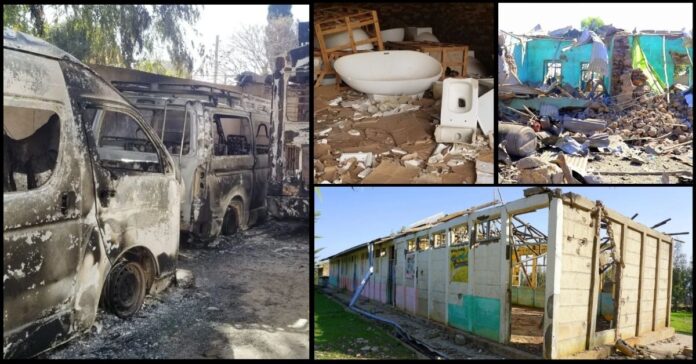

“The Eritrean Defense Forces (EDF) inflicted 56.3 percent of the total damage in the health sector, 43.9 percent in education, and 39.6 percent in culture and heritage” (CITG Social Sector Executive Summary, p. 14).

Meanwhile, the Productive Sector Report describes the EDF’s actions in extreme terms: “The Eritrean Defense Forces were responsible for widespread damage to agricultural infrastructure, irrigation systems, and machinery, particularly in the western and central zones of Tigray” (CITG Productive Sector Report, p. 211).

Later in the same document, the authors conclude: “The prolonged siege and blockade lasting more than two years led to widespread disruption of production goods and services” (p. 280).

The rhetorical pattern is unmistakable: the ENDF is portrayed as structured, bureaucratic, and state-directed in its destruction, while the EDF is depicted as visceral, vindictive, and irrationally cruel. This distinction is not analytical it is cultural and politically motivated.

III. The Cultural Coding of Blame: Prominent Tigrayan General Migbey Haile once remarked that among Eritrean forces, “lowlanders were more ruthless than highlanders.” For casual listeners, these terms sound geographic. Yet in the historical vocabulary of Tigrayan elites, lowlander refers to Muslim Eritreans from the coastal and western plains, while highlander denotes Christian Eritreans from the central plateau.

The implication carries an old prejudice: that Muslim Eritreans are inherently more violent, alien, and uncivilized. Such framing, when echoed in military rhetoric or academic reporting, imports sectarian assumptions into supposedly objective analysis.

When the CITG homogenizes the “Eritrean Defense Forces” as a singularly destructive actor, it unconsciously reproduces this hierarchy of perception the lowlander aggressor versus the highland victim. The data becomes an instrument of inherited prejudice disguised as quantification.

IV. The Pan-Tigrayan Lens: Embedded within parts of Tigrayan political and academic discourse is an enduring aspiration toward a “greater Tigrinya nation” a cultural and linguistic union that would blur the boundary between Tigray and Eritrea. This idea imagines Eritrea as a monolithic extension of Tigray, populated only by Christian Tigrinya-speakers, while its other communities are erased or diminished. In this ideological landscape, Eritrea’s independence is seen not as a decolonization victory but as a temporary detour from the supposed natural unity of the Axumite highlands.

Consequently, Eritrea’s sovereignty is not respected but resented. When Tigrayan elites craft narratives about the war, this resentment often seeps into their institutional language transforming post-war documentation like the CITG reports into expressions of cultural nostalgia and political reclamation.

V. Methodology as Ideology: The CITG claims to follow the UN-ECLAC Damage and Loss Assessment (DaLA) framework. However, this methodology was designed for natural disasters, not politically charged conflicts with contested territories. Several issues undermine the reports’ credibility.

The Productive Sector Report openly admits that: “Data was collected under the Tigray Interim Administration using structured surveys and institutional submissions. Western Tigray and parts of the eastern zone were excluded for security reasons” (CITG Productive Sector Report, p. 195).

That admission alone reveals a structural bias. The areas omitted are precisely those where alternative evidence or counter-narratives might have emerged. Moreover, the same document acknowledges that: “Over sixty percent of total loss is derived from projected future income rather than actual destruction” (p. 203).

By merging damage (physical loss) with loss (hypothetical income), the report inflates its estimates and turns speculative modeling into moral condemnation. The result is a pseudo-empirical weapon aimed at solidifying Tigray’s victimhood narrative.

VI. The Political Economy of Blame: The two CITG volumes serve three overlapping political purposes:

- Moral Capital: They establish Tigray as the preeminent victim deserving of global sympathy.

- Financial Leverage: The enormous damage valuation creates grounds for compensation claims against both Ethiopia and Eritrea.

- Diplomatic Isolation: By numerically quantifying Eritrea’s alleged share of destruction, the reports provide justification for renewed sanctions and exclusion from regional reconstruction forums.

Far from being neutral post-war audits, the documents operate as instruments in a wider contest for who controls the moral narrative of the Horn of Africa.

VII. What Is Erased: Eritrea’s Security Context: The reports omit the event that ignited Eritrea’s military engagement: the November 2020 TPLF attack on Eritrean border positions and Ethiopian Northern Command bases. This omission is not trivial it erases Eritrea’s right to self-defense and reframes its intervention as unprovoked aggression.

By detaching the data from the sequence of events, the CITG constructs a story in which Eritrea simply appeared in Tigray as an agent of destruction. It turns a defensive response to cross-border assault into a moral crime. This framing reveals how selective silence can be as powerful as selective evidence.

VIII. Consequences for Eritrea’s Sovereignty and Reputation: If left unchallenged, the CITG reports will harden into diplomatic “facts.” They risk cementing Eritrea’s image as a perennial aggressor, deterring foreign investment and overshadowing its role as a stabilizing force in the Red Sea corridor.

They also compress Eritrea’s plural national identity into a caricature homogenized, militarized, and stripped of nuance. Most dangerously, they normalize the idea that Eritrea’s sovereignty is conditional, subject to the moral verdict of neighboring elites and Western-aligned institutions.

IX. Conclusion: Beyond the Arithmetic of Accusation

The CITG reports will circulate through donor conferences, policy briefings, and transitional-justice debates. They will be cited by people who have never visited Eritrea but will speak with statistical certainty about its sins.

For Eritreans, the challenge is to read these numbers historically to recognize in them not objective truth but the repetition of a pattern: data as diplomacy, measurement as morality, and statistics as the new frontier of sovereignty.

True accountability in the Horn cannot be built on numbers alone. It must begin with context, integrity, and the courage to confront bias whether it hides in rhetoric, in data tables, or in the unspoken hierarchies of who gets to tell the story.