-

A Vision for a Free Africa

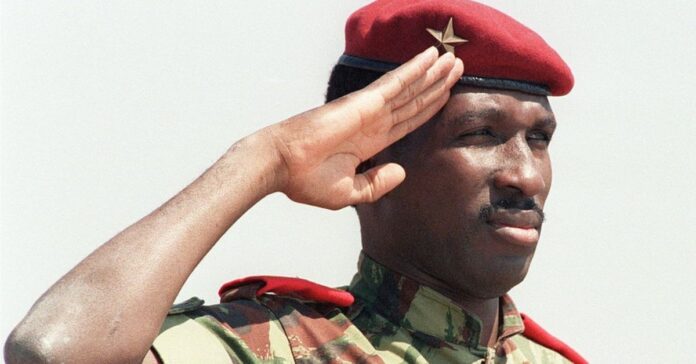

On October 15, 1987, Africa lost one of its most visionary sons. Thomas Sankara, President of Burkina Faso, was assassinated in a coup d’état orchestrated by his former comrade Blaise Compaoré—with the discreet complicity of French intelligence. His death was more than a political crime; it was the silencing of a dream. Sankara embodied the idea of a self-reliant and just Africa, free from the grip of debt, neocolonialism, and cultural domination.

Born in 1949 into a modest Catholic family that hoped he would enter the priesthood, Sankara chose the army instead—yet he redefined what it meant to be a soldier. He was a pacifist in uniform, a jazz guitarist in fatigues, a Marxist who refused dogma. His mind combined discipline and imagination, rigor and creativity.

In 1983, leading a group of young officers, he overthrew the pro-Western government of Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo. The following year, he renamed the country Burkina Faso—“the land of upright people”—thus symbolically severing ties with its colonial past. But Sankara’s revolution went far deeper than symbolism. “Our revolution cannot be imported or exported,” he declared. “It must be rooted in our own realities.”

He fought illiteracy, child labor, forced marriage, and female genital mutilation. He launched massive vaccination campaigns and planted millions of trees to halt desertification. To cut waste, he sold the government’s Mercedes fleet and replaced it with modest Renault 5s. He reduced his own salary and lived simply. More than anything, he spoke a new political language: one that ordinary people could understand—the language of African dignity.

2. Debt as the Modern Form of Slavery

Sankara was no romantic dreamer. He was a clear-eyed critic of economic dependency and a shrewd reader of global power. At the 1987 summit of the Organization of African Unity in Addis Ababa—just months before his death—he delivered one of the most prophetic speeches of the twentieth century.

“Debt,” he said, “is still colonialism, with the colonizers transformed into technical assistants. Those who lent us money are the same who colonized us—and now they want us to pay for our own oppression.”

For Sankara, debt was not a moral issue but a structural weapon. Paying it meant sentencing millions to poverty, depriving Africa of the means to fund schools, hospitals, and infrastructure. “If we don’t pay, our creditors won’t die,” he warned. “But if we do, we will.” His proposal was radical yet simple: a united African front refusing to repay illegitimate colonial debts, redirecting those resources to build their own future.

“Let us consume what we produce, and produce what we consume,” he urged—a principle that cut to the heart of Africa’s dependency. But such defiance was intolerable to the global order. Too independent for Paris, too socialist for Washington, too honest for his fellow African leaders, Sankara had become dangerous. His assassination was not merely a betrayal—it was a message to every leader who dared to imagine an Africa standing on its own feet.

3. A Concrete Pan-Africanism

What made Sankara different from many pan-African orators was his pragmatism. He did not romanticize Africa; he worked to rebuild it from within. In an era marked by the collapse of socialist experiments and the corruption of postcolonial elites, he sought to create a model of endogenous development—anchored in education, public health, gender equality, and environmental restoration.

He made women’s emancipation a cornerstone of his revolution. He appointed women to high office, outlawed polygamy in the civil service, and denounced patriarchy as a form of internal colonization. “There is no true revolution without the liberation of women,” he declared, turning feminism into a state policy long before it was fashionable to do so.

Sankara’s leadership was participatory and pedagogical. He explained public budgets in town squares and discussed policy in schools and marketplaces. Despite his authoritarian streak, his charisma inspired loyalty rather than fear. He represented a politics of service rather than privilege.

His pan-Africanism was equally grounded in action. He envisioned a continent united not by slogans but by shared projects and mutual accountability. “Those who indebted us,” he told his peers, “are the same who colonized us. We had nothing to do with this debt.” It was a declaration of intellectual sovereignty—a manifesto for a liberation Africa has yet to complete.

4. The Living Legacy of a Revolutionary

Nearly forty years after his assassination, Thomas Sankara remains one of Africa’s most revered and studied figures. His calm, lucid voice—captured in speeches and grainy recordings—still resonates in a world that has changed its forms but not its hierarchies. The multinational corporations he denounced continue to exploit African resources; foreign bases remain entrenched in the Sahel; public debts still strangle national budgets. Yet his legacy endures—not as a monument, but as a seed.

In Burkina Faso, where new generations of leaders invoke his name, Sankara has become a symbol of integrity and resistance. Across Europe, young people rediscover him as a rare example of moral coherence and visionary politics. His face adorns murals from Ouagadougou to Paris, his words echo in classrooms and songs. Like Che Guevara, he has become an icon—but unlike many icons hollowed by commodification, Sankara’s image retains its ethical force, alive and uncorrupted.

Thomas Sankara never demanded the impossible; he demanded justice. He believed that Africa could sustain itself, that freedom was not a gift but a conquest. And for that conviction, he gave his life—falling with a final cry: “You can kill Sankara, but you can never kill the ideas.”

Today, those ideas continue to walk on the feet of millions of young Africans who refuse to be debtors to anyone—except their own future.