Prefatory Summary: The Narrative According to the Ethiopian Reporter

In January 2021, the Ethiopian newspaper The Reporter published a lengthy article titled “Why Did Sudan Occupy the Ethiopian Border?” (ሱዳን የኢትዮጵያን ድንበር ለምን ያዘች?)

The piece framed Sudan’s reassertion of control in the al-Fashaga region as an act of aggression inspired by Egypt and encouraged by foreign powers.

That article is still prominently displayed at the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia | Institute of Foreign Affairs website, showing the symbiotic working relationship between the two.

According to the author — identified as a senior analyst at Ethiopia’s Institute for Strategic Affairs — Sudan’s actions were motivated by seven factors: an “un-demarcated border,” Egyptian pressure over the Nile and the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, Sudan’s internal political turmoil, supposed U.S. and Gulf support for Khartoum, Ethiopia’s temporary military weakness due to the Tigray conflict, and a lingering “sense of historic victory” dating back to the 19th-century Mahdist wars.

The article portrayed Ethiopia as a victim of opportunistic neighbors, unfairly targeted at a moment of domestic fragility. It proposed renewed bilateral dialogue and “informal diplomacy” by the Ethiopian diaspora to correct international misunderstanding. Nowhere did it acknowledge that the land in question lies west of the 1902 Anglo–Ethiopian boundary—a line accepted by both countries for nearly a century and still regarded as the international frontier.

This piece exemplifies a wider Ethiopian discourse: when neighboring states act within the limits of treaty boundaries, Ethiopian official media and policy circles often describe such actions as invasions. The contradiction between rhetoric and record provides the starting point for understanding Ethiopia’s territorial politics over the past three decades.

A Chronological Analysis of Map Expansion, Legal Defiance, and the Politics of Victimhood

- Imperial Legacy and the Colonial Boundary Framework (1900–1974)

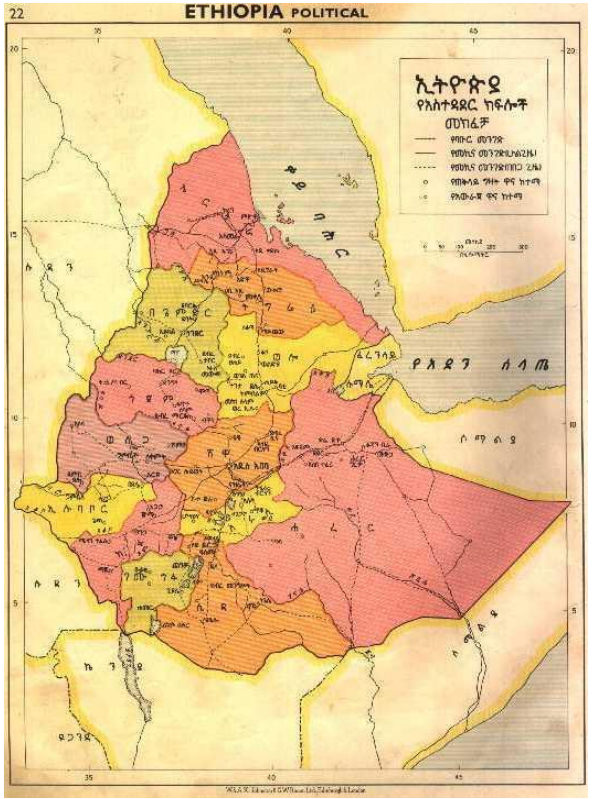

The modern territorial shape of Ethiopia was largely defined through a series of colonial-era treaties negotiated between Emperor Menelik II and the European powers that surrounded his empire.

The 1900, 1902, and 1908 treaties with Italy and Britain delineated Ethiopia’s northern and western borders with Eritrea and Sudan. Although rough in detail, these agreements established the principle of uti possidetis juris — the idea that colonial-era frontiers would be the starting point of modern sovereignty.

During the reign of Haile Selassie, Ethiopia largely respected these treaties while extending influence internally over peripheral areas such as the Ogaden and Gambella. The Emperor’s government saw itself as the guardian of African sovereignty against colonial partition and hosted the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, whose founding charter adopted the principle of respecting inherited boundaries.

In practice, however, Ethiopian administrations viewed these borders as flexible instruments of imperial security rather than as permanent frontiers. The notion that neighboring states occupied “historically Ethiopian lands” would become a recurring element in the political discourse of subsequent regimes.

- Revolutionary Turbulence and the Boundary Status Quo (1974–1991)

The Derg military regime maintained most of the imperial boundaries but was preoccupied with internal insurgencies. In the north, the Eritrean liberation struggle evolved into a full-scale war of independence. In the east, Ethiopia fought Somalia’s attempt to annex the Ogaden (1977–78).

The Derg’s foreign policy was grounded in the rhetoric of “anti-imperialist defense of territorial integrity.” Yet by the late 1980s, Ethiopian forces controlled only part of Eritrea, and the boundary with Sudan was effectively porous. The Derg’s collapse in 1991 opened the door for new boundary politics under the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF).

III. The EPRDF Era and the Redefinition of Boundaries (1991–1997)

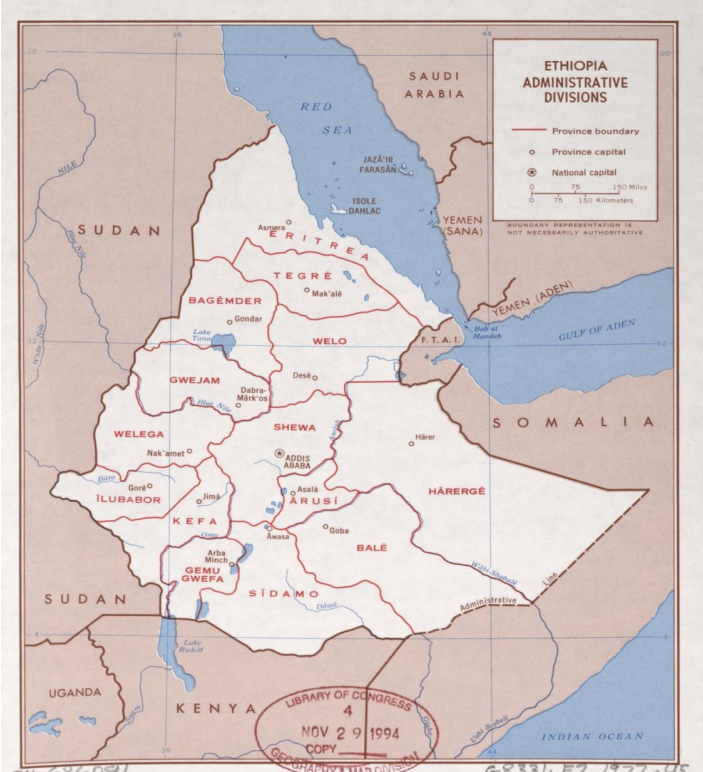

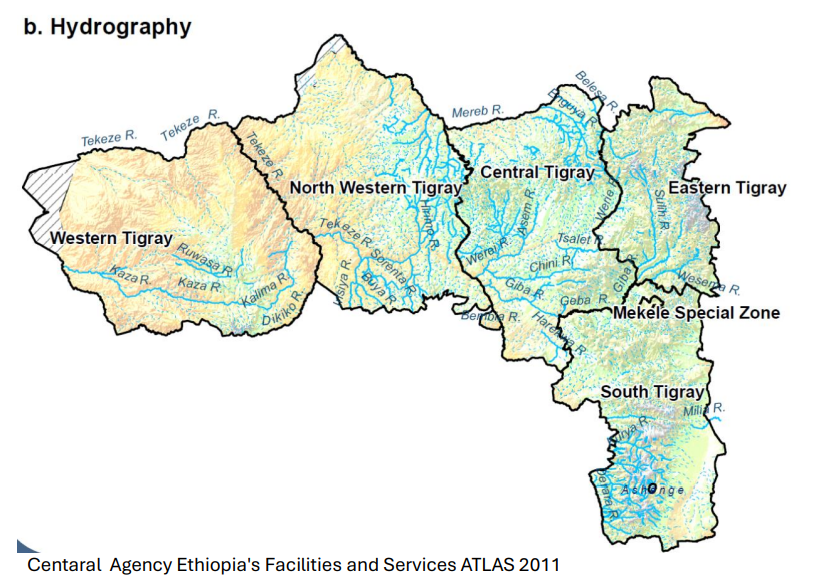

The EPRDF came to power with strong Tigrayan leadership and a revolutionary vision of ethnic federalism. One of its earliest administrative tasks was to produce new regional boundary maps for the federal republic. Between 1993 and 1997, the Ethiopian Mapping Authority issued a series of revised atlases that quietly shifted Ethiopia’s northern and western borders.

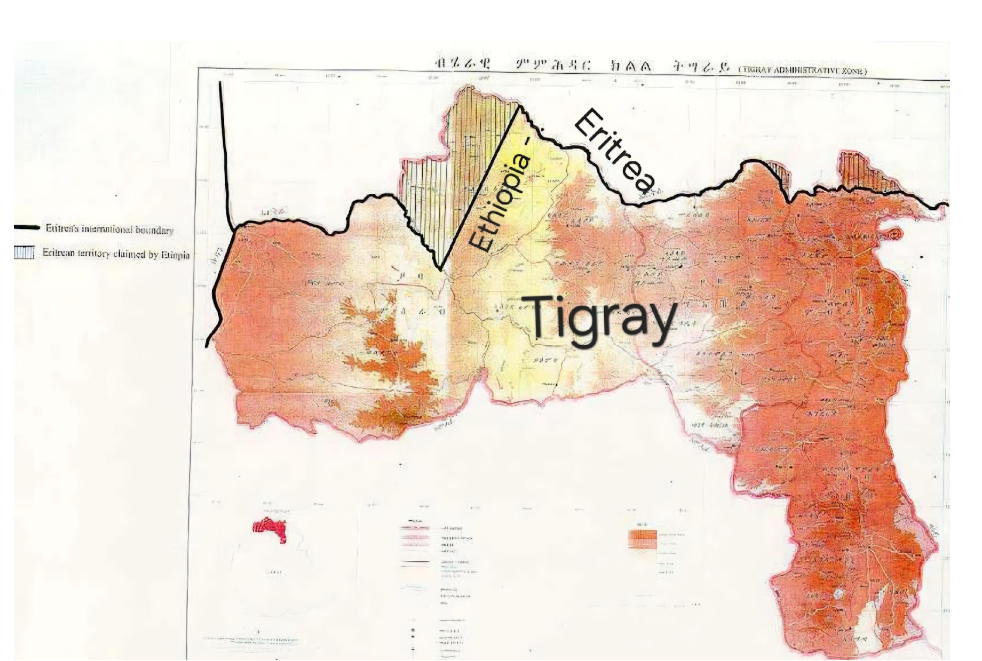

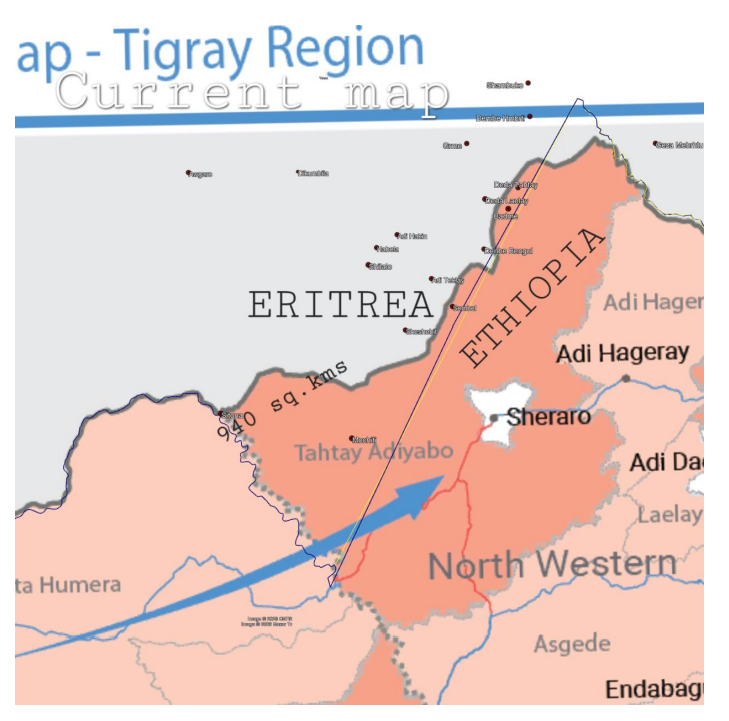

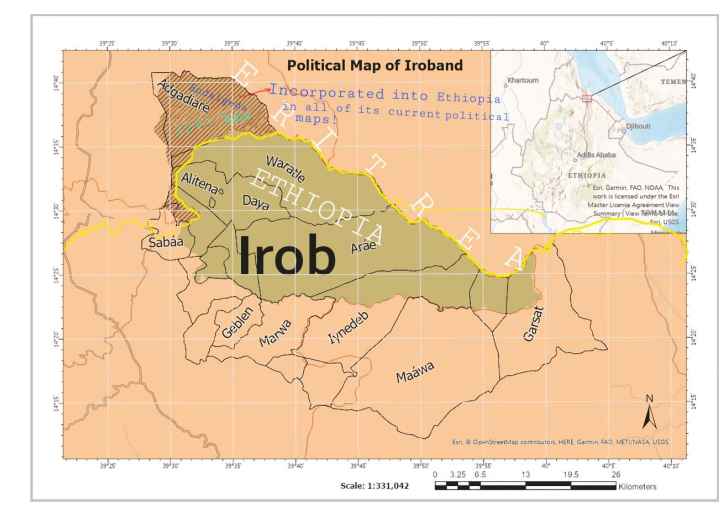

In the north, the Tigray Region was mapped to include Badme, the Irob highlands, and the Mereb–Belesa corridor — all territories historically administered from Eritrea under the 1900–1908 treaties. In the west, Amhara regional maps extended beyond the 1902 Anglo–Ethiopian line into Sudan’s al-Fashaga and Gallabat districts.

These changes were presented as “administrative rationalization” after the fall of the Derg, but they marked the beginning of a new expansionist pattern: unilateral cartographic incorporation of territories that lay outside Ethiopia’s internationally recognized boundaries.

- The Eritrea War and the Birth of a Victim Narrative (1998–2002)

The publication of Ethiopia’s 1997 national atlas triggered formal protests from Eritrea, which viewed the inclusion of Badme and other northern villages inside Tigray as a violation of the 1900 boundary treaty. Tensions escalated into the Eritrea–Ethiopia war (1998–2000).

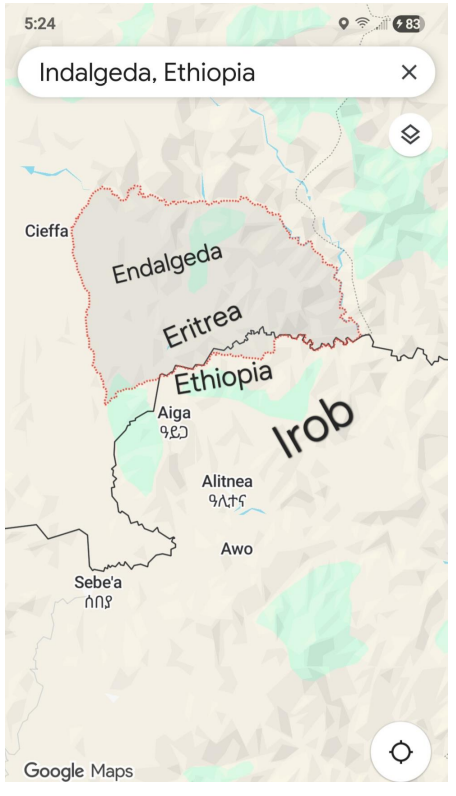

Ethiopia framed the conflict as a response to an “Eritrean invasion” of its territory, a claim that resonated with domestic audiences but contradicted earlier map alterations. The subsequent Eritrea–Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC) — established under the Algiers Agreement of December 2000 — investigated the historical treaties and ruled in April 2002 that Badme, Irob (Endalgeda), and the Mereb–Belesa sector belonged to Eritrea.

The EEBC’s ruling was “final and binding” under international law. Eritrea accepted it; Ethiopia rejected implementation while claiming to “accept the decision in principle.” This legal paradox — acknowledging the authority of the court while refusing compliance — set the tone for the next two decades.

- Post-2002: Legal Defiance and Cartographic Entrenchment (2002–2018)

After 2002, Ethiopia continued to occupy the EEBC-awarded territories while publicly portraying Eritrea as the intransigent party. The official narrative emphasized peace and dialogue, but national atlases and administrative datasets retained the pre-2002 maps, depicting the awarded areas as part of Tigray.

Internationally, Ethiopia’s refusal to implement a binding ruling eroded its moral standing as a champion of African unity. Domestically, however, the stance served a nationalist purpose: it reinforced a sense of victimhood and external encirclement that successive governments used to consolidate internal unity.

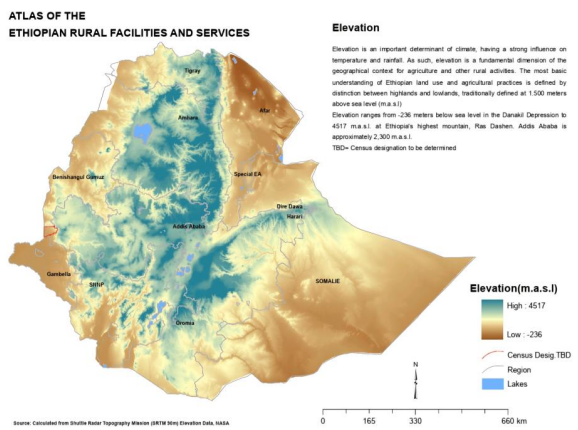

Meanwhile, the same cartographic approach appeared on the western frontier. In Amhara regional maps and the 2011 “Atlas of Rural Facilities and Services”, large portions of Sudan’s al-Fashaga and Gallabat were shown inside Ethiopia. These maps normalized the post-1995 occupation of fertile Sudanese farmland by Ethiopian settlers protected by local militias.

- The Al-Fashaga Question and the Return of the Pattern (1995–2025)

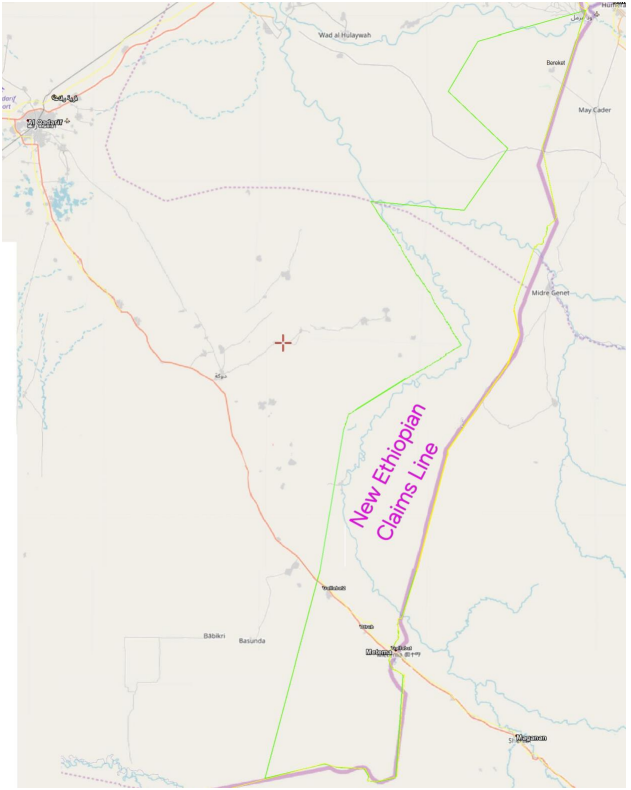

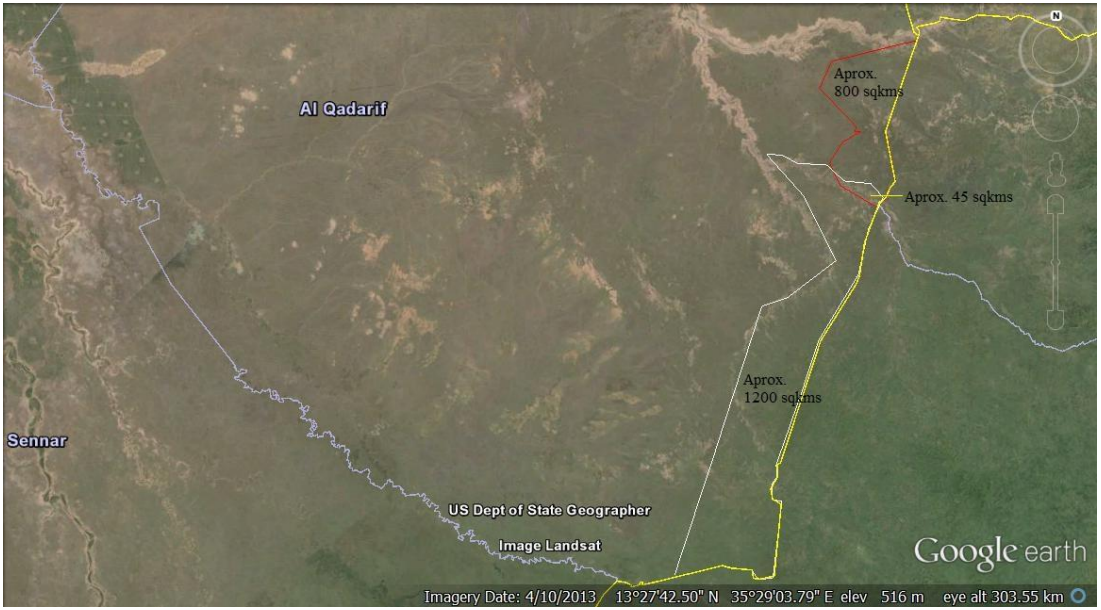

The 1902 Anglo–Ethiopian Agreement fixed the western boundary clearly along a surveyed line that has been recognized internationally ever since. For decades, both sides respected it. The situation changed in 1995, when Sudan’s internal instability after the attempted assassination of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in Addis Ababa created a security vacuum.

Ethiopian regional forces and Amhara militias moved westward, seizing al-Fashaga, Jabal al-Tayyar (Mount Dagleish), and Gallabat. For over two decades, Ethiopian farmers cultivated these lands under local administration, while Addis Ababa insisted that the border was “un-demarcated.”

Sudan, meanwhile, maintained its adherence to the 1902 line. When Ethiopia became engulfed in the Tigray conflict in 2020, Sudanese forces re-entered the disputed zone to restore control up to the treaty boundary. Ethiopia denounced the move as a “Sudanese invasion,” reproducing almost word-for-word the victim narrative used against Eritrea twenty years earlier.

By 2025, diplomatic negotiations remain frozen: Sudan insists on the 1902 boundary, while Ethiopia demands joint demarcation — a tactic that effectively postpones withdrawal and sustains its claims.

VII. The Broader Regional Context

Ethiopia’s conduct stands in contrast to the continental principle of respecting inherited borders, articulated in the OAU Resolution AHG/Res.16(I) of 1964. That principle — uti possidetis juris — became the foundation of Africa’s post-colonial stability.

Ethiopia, ironically a founding member of the OAU, has violated that very principle more than once.

In the Ogaden (eastern Ethiopia), Addis Ababa uses Somali irredentism to justify heavy militarization and strict control, even though the boundary with Somalia was long settled by the 1897 treaty. In the north and west, it alters maps and defends the resulting disputes as acts of self-defense.

This duality — expansion in fact, victimhood in narrative — has characterized Ethiopia’s external relations since the 1990s. It secures domestic legitimacy but undermines regional trust.

VIII. International and Legal Assessment

International law is clear:

Boundaries established by colonial treaties remain binding unless both parties agree otherwise or an international tribunal revises them. Ethiopia’s actions along both the Eritrean and Sudanese frontiers therefore amount to unilateral alterations of recognized international boundaries, a breach of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969) and of the African Charter principle of territorial integrity.

When Eritrea and Sudan reasserted control over these areas — through the EEBC enforcement in the north and through troop deployment in al-Fashaga — they were acting within the limits of their legal boundaries, not as aggressors.

- Consequences for Ethiopia’s Diplomatic Credibility

Ethiopia’s pattern of map manipulation and defensive rhetoric has had three major consequences:

- Erosion of Legal Credibility: Having refused to implement a binding international decision, Ethiopia weakened its position to invoke international law against its neighbors.

- Regional Distrust: Both Eritrea and Sudan view Ethiopia as a boundary revisionist power rather than a reliable partner.

- Loss of Moral Authority: Ethiopia’s long-standing image as Africa’s symbol of anti-colonial integrity now sits uneasily beside its record of disregarding colonial boundaries when inconvenient.

- Conclusion

Over the past three decades, Ethiopia has followed a consistent sequence in its border relations:

- Cartographic Expansion – Redefining maps and administrative units beyond treaty lines.

- Legal Defiance – Rejecting or stalling the enforcement of international boundary rulings.

- Victim Narrative – Portraying neighborly reassertions of borders as external aggression.

This pattern emerged in the Eritrean frontier (1997–2002), reappeared in the Sudanese borderlands (1995–2025), and echoes even in Ethiopia’s handling of its eastern Somali frontier.

It reveals a state simultaneously invoking international law for protection while quietly reshaping borders in its favor — a contradiction that has become central to Ethiopia’s regional diplomacy.

Until Ethiopia reconciles its mapmaking practices with the legal boundaries it helped codify through the OAU, it will continue to oscillate between being the architect of African territorial integrity and its most persistent violator.

- The Role of International Actors and Institutional Weakness

The international system’s uneven enforcement of boundary law has been a major reason Ethiopia has been able to maintain de-facto control over disputed territories for so long. The issue is less deliberate conspiracy than a pattern of institutional incentives, data inertia, and diplomatic caution that together have produced permissive conditions.

- Diplomatic Calculus in the Horn of Africa

Ethiopia has long been a strategic partner for peacekeeping, counter-terrorism, and humanitarian logistics. Because Addis Ababa hosts the African Union and the UN’s main regional offices, Western governments and the UN Secretariat have often treated it as an indispensable interlocutor. This has generated a reluctance to apply sanctions or explicit cartographic corrections that might be interpreted as hostile acts. In practice, the desire to preserve Ethiopia’s cooperation in regional security has outweighed the enforcement of boundary rulings.

- The UN’s Administrative Neutrality Trap

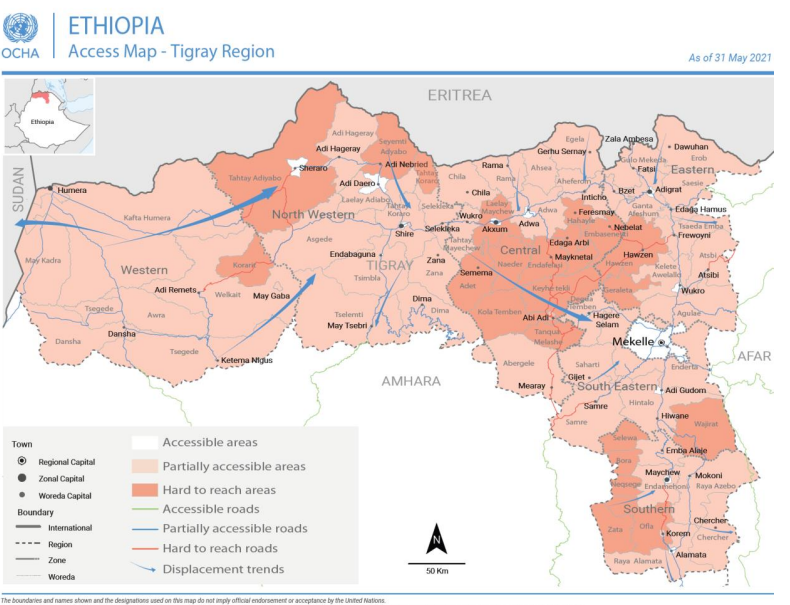

After the 2002 Eritrea–Ethiopia Boundary Commission award, the UN Cartographic Section adopted a policy of non-publication of political maps for both states until physical demarcation could occur. The intention was neutrality, yet the outcome was paralysis: by withholding maps, the UN avoided acknowledging Eritrea’s legal entitlement, while UN field offices continued to operate with Ethiopia’s pre-2002 administrative datasets. The same occurred along the Sudanese border, where humanitarian agencies used Ethiopian regional polygons for logistical convenience. The technical neutrality thus translated into de-facto acceptance of unlawful maps.

- Data Supply Asymmetry

UNOCHA and other humanitarian agencies depend on “Common Operational Datasets” supplied by host governments. Eritrea does not provide such datasets, while Ethiopia does. The result is a data asymmetry: all operational cartography in the Horn of Africa is anchored in Ethiopian, not Eritrean, shapefiles. Humanitarian mapping therefore reproduces Ethiopia’s version of boundaries, not because of policy preference but because of available data. Over time this has normalized the expanded Ethiopian map in international information systems.

- Western Development Agencies

Large development partners—USAID, the EU, and the World Bank—use Ethiopian government base maps for infrastructure and agricultural projects. These datasets incorporate disputed areas such as al-Fashaga and Badme within Ethiopia’s project zones. The repetition of those boundaries across donor reports and GIS portals gives them a quasi-official international appearance, even though they contradict international law. None of these institutions possess an enforcement mechanism to require alignment with treaty boundaries.

- Selective Enforcement and Global Politics

Elsewhere—Crimea, Northern Cyprus, Western Sahara—the UN and major powers have insisted on strict cartographic conformity with legal boundaries. In the Horn of Africa, by contrast, the same actors have tolerated ambiguity in the name of humanitarian access and regional stability. The inconsistency has weakened the authority of uti possidetis juris and encouraged Ethiopia to view map manipulation as a low-risk diplomatic strategy.

Summary

The persistence of Ethiopia’s boundary practices cannot be explained by national policy alone. It reflects a broader international environment that prizes stability and access over legal precision. Through administrative inertia, risk avoidance, and dependence on host-country data, the UN and major donors have unintentionally reinforced Ethiopia’s portrayal of contested territories as domestic space. This has allowed an unlawful status quo to harden into apparent normality, at least in global information systems.