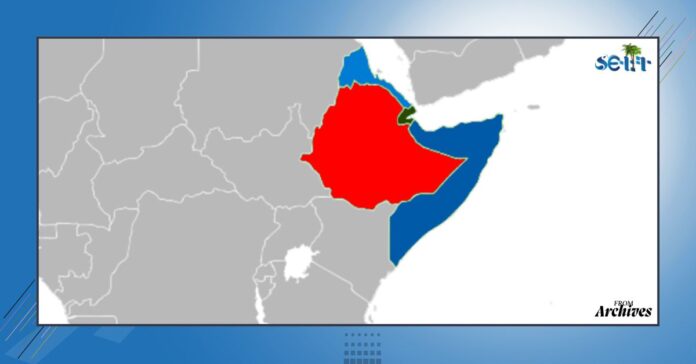

The Horn of Africa is widely recognized as one of the most conflict-prone regions in the world, characterized by persistent disputes both within and between states. The root causes of these conflicts are multifaceted and complex, generally stemming from two main factors: local expansionist agendas and foreign intervention. The current Ethiopian Prime Minister’s insistence that Ethiopia must become a coastal state has not only intensified regional security concerns but also fueled a campaign that can only be described as warmongering. This stance serves neither Ethiopia nor the broader region, as it risks further destabilization, strains relations with neighboring countries, and undermines efforts toward regional cooperation and lasting peace.

Foreign Intervention and Its Impact

Foreign involvement in the Horn of Africa dates back to ancient times, when major powers vied for control over the Red Sea—a crucial trade route to Asia. For the purposes of this discussion, however, the focus is on the post-World War II dynamics that have shaped the region’s geopolitical landscape, particularly regarding Eritrea.

Eritrea, which had the potential to become the first independent African nation, was denied this opportunity and was instead federated with Ethiopia—a decision driven largely by Cold War-era geopolitical calculations by the United States. Viewing Ethiopia as a strategic ally, the U.S. played a decisive role in incorporating Eritrea into Ethiopia. Although the UN resolution used to justify this action is well documented, its ultimate consequence was a 30-year war for Eritrean independence, culminating in victory in May 1991. This outcome was legally confirmed through a UN-supervised referendum in April 1993, in which 99.8% of Eritreans voted for independence. Nonetheless, the war inflicted tremendous human and economic losses, significantly hindered the development of both nations for decades.

Ethiopia’s Expansionist Agenda

Ethiopia has long claimed a historical right to coastal access, basing its argument on narratives that distort historical realities. While several pre-colonial kingdoms and civilizations in the Horn of Africa enjoyed maritime access, these entities belong to a different era and do not correspond to modern Ethiopia. At best, they represent a shared heritage that could foster regional integration. A key flaw in Ethiopia’s argument—repeated by its politicians and intellectuals—is the assertion that Ethiopia, as a nation-state, has existed for thousands of years in its current territorial configuration.

In reality, modern Ethiopia, like other African states, was significantly shaped by European colonialism, particularly following the Berlin Conference (1884–1885). The present-day borders of Ethiopia are largely the result of territorial expansions under Emperor Menelik II in the late 19th century, formalized through colonial treaties with Italy (which established the Eritrean border), Britain (which defined the Sudanese and Kenyan borders), and France (which delineated the boundary with Djibouti). These agreements cemented Ethiopia’s landlocked status and remain the foundation of its modern territorial framework. Any attempt to challenge these established borders risks undermining the stability of the entire Horn of Africa.

The Risks of Historical Revisionism

The Ethiopian Prime Minister’s efforts to invoke pre-colonial history to justify claims to a seaport ignore the fact that Ethiopia’s territorial boundaries—like those of all African nations—are rooted in the colonial era. Should Ethiopia challenge these colonial-era borders in pursuit of maritime access, it would not only reignite disputes with Eritrea but could also spark broader territorial conflicts with Sudan, Somalia, Kenya, and Djibouti. Such revisionism sets a dangerous precedent, encouraging other nations to revisit historical grievances and potentially escalating conflicts.

Moreover, these claims run counter to international law and the cardinal principles of the African Union Charter, which considers colonial borders sacrosanct. More importantly, they prolong the suffering of the peoples of the Horn of Africa. The Ethiopian leadership repeatedly asserts that it seeks to achieve maritime access through peaceful means, yet the notion of acquiring a seaport without coercion is inherently contradictory. If Ethiopia is so confident in its legal entitlement, why not pursue the matter in an international court instead of resorting to inflammatory rhetoric? This was, in fact, attempted after the 1998–2000 war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, when arbitration reaffirmed Eritrea’s sovereignty over its ports based on colonial treaties. This persistent insistence on maritime access without clear legal justification only deepens distrust and tension, potentially paving the way for another devastating conflict.

The Path Forward: Diplomacy and Economic Cooperation

Rather than seeking to revise established borders, Ethiopia’s most viable path to maritime access lies in diplomacy and economic cooperation with its coastal neighbors. Pragmatic strategies—such as comprehensive trade agreements and robust regional partnerships—offer far more sustainable solutions than territorial revisionism.

Ethiopia has already demonstrated its potential for economic cooperation through access to Djibouti’s ports and recent agreements with Somalia and potentially with Eritrea. Expanding and formalizing these arrangements through long-term contracts, significant infrastructure investments, and comprehensive regional trade pacts would ensure secure and uninterrupted access to the sea. Furthermore, investing in regional integration mechanisms, such as the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), would allow Ethiopia to deepen its economic and political ties with its neighbors while bolstering regional security and stability.

By prioritizing economic integration and diplomatic engagement, Ethiopia can secure its maritime trade interests while contributing to overall regional stability, fostering a cooperative environment in the Horn of Africa rather than exacerbating existing tensions. The long-term prosperity of the region depends not on historical revisionism or expansionist rhetoric but on mutual respect, economic cooperation, and collective security. The Horn of Africa has long been a victim of both foreign intervention and local expansionist ambitions, which continue to prioritize external agendas over the urgent need for regional peace and cooperation. Unless regional leaders break free from these influences and commit to a truly collaborative framework, the cycle of conflict and instability will persist to the detriment of all nations in the region.